One of my favorite things about being an author, aside

from sharing my stories with readers, is all the wonderful information I find

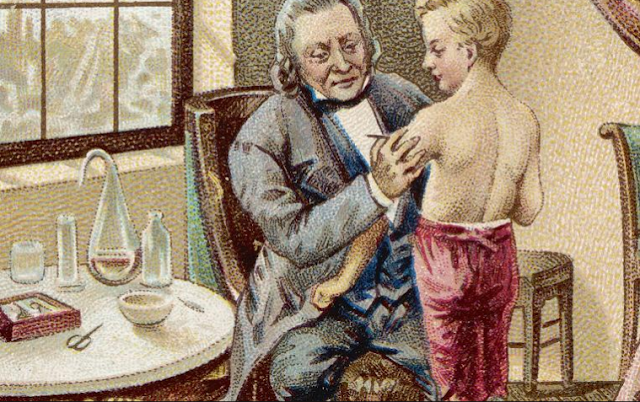

while doing research. Writing The Illegitimate Duke allowed me to

dive back into Regency medicine, an area that first caught my interest seven

years ago when I started work on There’s Something About Lady Mary.

What intrigues me just as much now as it did back then, is discovering how

advanced some physicians and surgeons were in the past. They weren’t all the

blood-letting quacks so often depicted in the movies. For instance, I bet it

would surprise you to know that the first successful heart surgery on record,

was performed by the Spanish surgeon, Francisco Romero, in 1801! Granted, he

‘only’ worked on the lining of the heart in order to drain excess fluid, but he

did this twice without either patient dying. And don’t forget that this was

done at a time before anesthesia, which is really quite amazing. Unfortunately,

finding information on Francisco Romero wasn’t easy. It required a bit of

digging and eventually I just stumbled upon him by chance. If you do a search

for ‘history of heart surgery’ or ‘first heart surgery’ etc. other more recent

surgeons are credited, which in my opinion is rather unjust.

“Delayed acceptance of discovery happens in

all areas of science, of course, but it always happens in the field of medicine

with great poignancy, since there the human costs of dropping the technological

ball are usually great.”

– Alcor. Life Extension Foundation

Similarly, Charles Kite and William Buchan were medical

pioneers who ought to be household names. Instead, other people are more

famously known for discoveries and claims these men made long before anyone

else. I bet it would surprise you to know that the first cardiac defibrillation

was given to a three year old girl on July 16th 1774, long before Jean-Louis Prevost and Frederic Batelli demonstrated the use of defibrillation

in 1899. When Catharine Sophie Greenhill fell out of a first floor window, an

apothecary pronounced her dead. Thankfully, a neighbor named Squires, an

amateur scientist, arrived on the scene twenty minutes later with an

electrostatic generator and proceeded to pass electricity through her body.

History records that after giving her several shocks to the chest, her pulse

reappeared and she began breathing again. Eventually, after a short time in

coma, she recovered fully.

This incident is remarkable and this is where Charles Kite comes

in, because he took note. As a member of the Humane Society (still in existence

today and originally named The Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned), he not only

advocated the resuscitation of people in cardiac arrest by using bellows as

well as oral and nasal intubation, but also developed his own electrostatic

revivifying machine. This used Leyden jar capacitors in a similar way to the DC

counter shock of the modern cardiac defibrillator, which makes you stop and

think, doesn’t it? I mean, we’re still talking late 18th Century here

since Kite received a silver medal for his work in 1788.

In The Illegitimate Duke, the hero, Florian Lowell, is a very

progressive man of medicine who has traveled the world and likes to keep up to

date with new discoveries. Through him and his conversations with the heroine, Juliette

Matthews, it is my hope that Charles Kite will be brought to people’s attention

and remembered for his extraordinary contribution to both science and medicine.

The same can be said about

William Buchan. I have used his book, Domestic

Medicine, as the foundation for Florian’s knowledge about hygiene. He even

lends the book to Juliette and advises her to read it. This is because it

really aggravates me when the wrong person is acknowledged for an achievement.

While the Hungarian physician, Ignaz

Philipp SemIgnaz (1818-1865), did find the connection between the handling of

corpses and puerperal fever in childbirth, he is not the first person to

discover the significance of hand washing, even though his finds in this area

did result in greater attention to cleanliness in operating rooms.

Because

here’s the problem with that theory: William Buchan wrote about the importance

of hand washing in Domestic Medicine, first published in 1772, where he says:

Were every person, for example, after

handling a dead body, visiting the sick, etc, to wash before he went into

company, or sat down to meat, he would run less hazard either of catching the

infection himself, or communicating it to others.

Buchanan

also mentions the importance of cleanliness aboard a ship where escaping an

epidemic would be difficult. In this context, he advises that if infectious

diseases were to break out, cleanliness is the most likely way to prevent it

from spreading. This includes the washing of all clothing and bedding used by

the sick as well as fumigation with brimstone or the like.

In

The Illegitimate Duke, Florian

applies these methods during a typhus outbreak. He uses tar water instead of

brimstone, however, and cleans the quarantine ship with a solution of lime, as

implemented by the Edinburgh Infirmary and advised by practitioners of the

Royal Army and Navy during the early 19th Century. Furthermore,

inspiration for the treatment of typhus was found in the Edinburgh Infirmary’s insistence

that patients be stripped of their clothing, given haircuts to remove lice (which

would have been helpful since typhus was spread by lice, though this wasn’t

known until Charles Nicolle made the connection in 1903) given a bath and in

some cases rubbed with mercurial ointment.

Florian

also uses morphine, a narcotic that wasn’t commercially available in 1821 when

the story takes place, even though it had been produced in Germany by pharmacist Friedrich Sertürner in 1804. I like to think that Florian corresponded

with Sertürner who happily supplied him with

morphine after Florian carried out his own tests. This attention to detail and

willingness to stay apprised of medical advancements is what makes Florian such

a wonderful physician and hero.

When asked how he came by

his profession, he responds:

“Saving lives is a never- ending struggle

against the evils of the world. The things I have seen have changed me in ways

I am not always fond of. When I began my apprenticeship, I was sixteen years

old and used to a life of leisure and luxury. Seeing a boy my own age lose a

limb that first day was shocking. I confess I fled the operating room to cast

up my accounts.”

“And the boy?”

“He died three days later from infection.”

Florian’s voice was strained with emotion. “I made it my purpose then and there

to discover the best methods of medical treatment and surgery. Forced to

complete my apprenticeship in order to be admitted into Oxford, I

dedicated my free time to reading medical texts and interviewing not only other

physicians, but anyone I could find who had traveled abroad and born witness

to successful surgeries.”

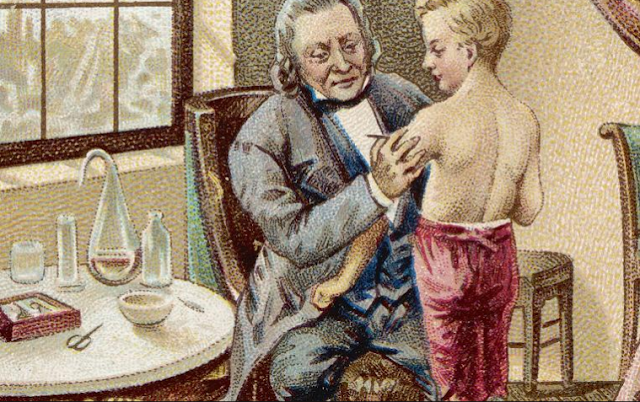

Since Florian had the

funds to attend university and I don’t go into detail, this doesn’t really

convey how easy it was to gain a medical education and start your own practice prior

to 1815. Apprenticeships for physicians, apothecaries and surgeons were

extremely popular. No examination was required at the end, which lead to a huge

imbalance in student competence, depending on who the teacher had been.

Like Florian, many

aspiring physicians did attend university since this added an element of

prestige to their profession. But obtaining a degree did not require the sort

of hands on experience one might expect. It focused mostly on writings

of physicians from classical times such as Hippocrates and Galen and on the

student’s ability to defend two theses before the Professor of Medicine in

Latin. Shockingly, however, it was quite acceptable for the student to pay

someone to do this for him.

Some of this leniency changed after 1815, at least for

the apothecaries who were now obligated to adhere to the Apothecaries Act. Enforced

by the Society of Apothecaries and requiring qualifying examinations, its main

features were:

• The Society of Apothecaries became the main

examining body for entry into general medical practice

• A five year apprenticeship was compulsory

• The holder of the Licence of the Society of

Apothecaries (LSA) must be willing to dispense physicians' prescriptions

• The LSA was compulsory for all who dispensed

It seems that because of

the lack of regulations during most of the nineteenth century, ridding the

medical community of quacks and ensuring high levels of skill, was an uphill

battle. Even so, there were some remarkable physicians and surgeons who were truly

dedicated to their work and to their patients, such as Charles Kite and

Franciso Romero. These are the men on whom Florian is based – on the men who

saw medicine as a vocation instead of simply a way in which to make a living.